One of the aims of The 99 Names of God is to help children, parents, and teachers build a spiritual link to the natural world, making us aware that God communicates to us through nature in the most beautiful, awesome, playful, and sublime manner. Young and old are encouraged to see how we learn spiritual and ethical lessons in the natural world, how we are nourished by it inwardly and outwardly, and that outside of the human soul, it is nature that is the ultimate playground for the manifestation of Allah’s Names.

Hand-in-hand with this aim goes an attempt to build ecological awareness. Mainstream secular education is at pains to educate our children on our responsibilities in the face of environmental crisis. Yet the nature presented there is often a superficial thing separate from us and without spiritual significance. How much more invested we become when we understand the profound meaning within nature, and our intimate spiritual connection to it. Ecological awareness becomes a matter of love.

At Chickpea Press, we believe all religions can help foster a spiritualised ecology. The Quran is replete with exhortations for us to take care of the earth and witness its grandeur, beauty, and symbolism. Yet we might ask: How much does the religious education that Muslim children currently receive aid this process? Will they, and do we, have the ecological awareness and determination to stand up to corporate greed and heedlessness, whether at a major crisis point like Standing Rock or in our back yard?

When exploring signs of the Name al-Muqit (the Nourisher), our book offers this reflection:

We use figures from Islam’s rich heritage in order to further explore each Name. For al-Muqit we offer this from Rumi[i]:

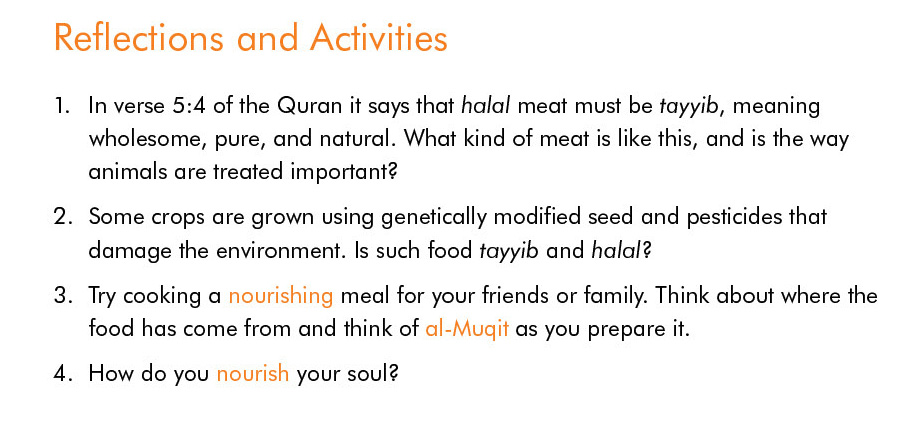

We also suggest reflections and activities related to each Name. With al-Muqit we suggest the following:

Giving an equal balance to male and female voices is also of great importance to us, especially given the history of gender imbalance in Muslim societies and the world at large, an imbalance that is at odds with the true spirit of Islam. As has often been suggested, perhaps there is a very real connection between the exploitation of the natural world and the exploitation of women, for it is not without reason that we speak of “Mother Nature”. We might remember that the words “mother” and “matter” both spring from the same Latin root, and man’s egotism has often striven to bend both to his will rather than harmonise with them.

So The 99 Names of Allah gathers wisdom from strong spiritual women such as Khadijah, Fatimah, Aishah, Rabiah, Nafisah, Shawana, and many more. Rabiah illustrates the Name al-Hamid (the Praiseworthy)[ii]:

Perhaps building a relationship with feminine wisdom and Mother Nature can help us regain a sense of God’s immanence within creation, which all too often has been neglected in Islamic education in favour of stressing God’s transcendence. This is not to say that we do not also find signs of God’s transcendence in nature. Stern, perhaps masculine, Divine Attributes manifest in nature as well as feminine ones (for instance, mountains remind us that God is the Highest, al-Aliyy, or a majestic lion reminds us God is the Sovereign, al-Malik). However, taken as a whole, nature strikes us as feminine, perhaps because we associate it primarily with the receptive earth. And it is the feminine, receptive aspects within ourselves, whether man or woman, from which humanity as a whole is currently most estranged. But there are encouraging signs: the recent Women’s Marches around the world are surely a sign that the Divine Feminine is stirring.

One of the effects of the current imbalance is that we place too much emphasis on doing at the expense of being. We feel that we must constantly be busy, mindlessly consuming more and more, and constantly plugged into the latest and fastest technology. We are scared of silence and that emptiness where something might grow. Much of modern popular culture, with its inane distractions, is at pains to wall us off from this beautiful inner space.

To help alleviate this, The 99 Names of God reminds parents and teachers of Islam’s rich meditative tradition, known as muraqabah. Muraqabah means “watchfulness” and comes from the same root as a Divine Name, ar-Raqib, the Watchful. It was practised by the Prophet and his companions after salah, and is well-known to the Sufis. It is a watchfulness of one’s inner states, an exercise in simply being and witnessing. And so, in relation to ar-Raqib, we suggest the following:

Muraqabah

Sit in a comfortable position and focus on your breath – its gentle rise and fall. After a little while, relax your shoulders, let your hands lie still and become aware of everything in the room. Then watch your inner feelings – are you calm or tense, happy or sad? Don’t worry, just accept how you feel and hand those feelings over to Allah. Next, watch the thoughts passing through your mind. Be aware that you are not your thoughts; they just pass through you. You can hand them over too. Eventually, let your mind sink into your heart which is a peaceful eye watching over everything.

Modern studies have shown that meditation not only improves student wellbeing, it also improves student performance, so cultivating being actually helps us become more effective doers.

In one of our previous posts on The Living Tradition, called “Feminine Symbols in Islam”, Mahmoud Mostafa offered us this fascinating insight into Muhammad’s title Nabiyy-ul Ummiyy: “… this term is often understood and translated as the unlettered prophet or the gentile prophet but Ummiyy literally means of the mother or the motherly and it refers to the fact that he received wisdom and guidance directly from the source, from the Mother, not from books or from other men.”

We might ask ourselves: what is this receptivity of soul that Muhammad possessed and how might we teach our children to emulate it? The 99 Names of God is a humble attempt to begin to answer this and, in so doing, aims to contribute to a more balanced, holistic approach to Islam.

The 99 Names of God is printed on paper certified by the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) using vegetable-based inks.

This article was first published on Patheos Muslim.

[i] Rumi’s poetry first published in The Rumi Daybook: 365 Poems and Teachings from the Beloved Sufi Master by Rumi (trans. by Camille and Kabir Helminski, Shambhala Publications)

[ii] Rabiah’s poetry first published in Doorkeeper of the Heart: Versions of Rabi’a (trans. Charles Upton, Threshold Books)